Painting of a Taino Indian found at Caguana Indigenous Ceremonial Park in Utuado, Puerto Rico

The Taíno Indians, where are they today?

After reading a book titled Mi Pueblo Taíno, (My Taíno People), by Rafael González Muñiz, my mind was filled with curiosity. In a very inspirational yet factual way the author shares with his readers a glimpse into the Taíno culture: what they were like, their historical background as well as sharing with us some details about the extensive preservation work of the Taíno culture being done in his native Puerto Rico.

Mi Pueblo Taíno is more than an introduction to the Taíno tribes that once inhabited the Greater Antilles in the Caribbean. This is not a history book trying to teach its reader about one of the so called lost tribes of the new world. Nor is it a complicated and scholarly written anthropology tome trying to present factual information in a scholarly dry monotone. González Muñiz’s book is an invitation to get to know one of the most intriguing and neglected indigenous groups of people that inhabited the island of Boriquén.

But who were these people? How come most Puerto Ricans often pride themselves in tracing their lineage back to them? And why does their culture permeates every corner of the island of Boriquén to this day?

petroglyph of a woman figure

As a visitor to this fascinating island I can’t help but wonder: where are the Taíno Indians? Were they really exterminated by the European Conquistadors? Why do Puerto Ricans talk about them as if they were still alive? As I traveled throughout the island, I can see traces of native features amongst the general population, but finding someone who fully personifies the Taíno physical traits is hard. Puerto Rico has been a melting pot of cultures before the term melting pot even existed: from Europe to the Middle East and from Asia to the Americas, all ethnic groups across the world have left bits and pieces of their cultural makeup in this bright Caribbean island. Still, I hear the stories again and again as I travel across the island about someone’s aunt or uncle or grandfather or brother who are proof, if proof were needed, that the Taínos still live in Boriquén to this day.

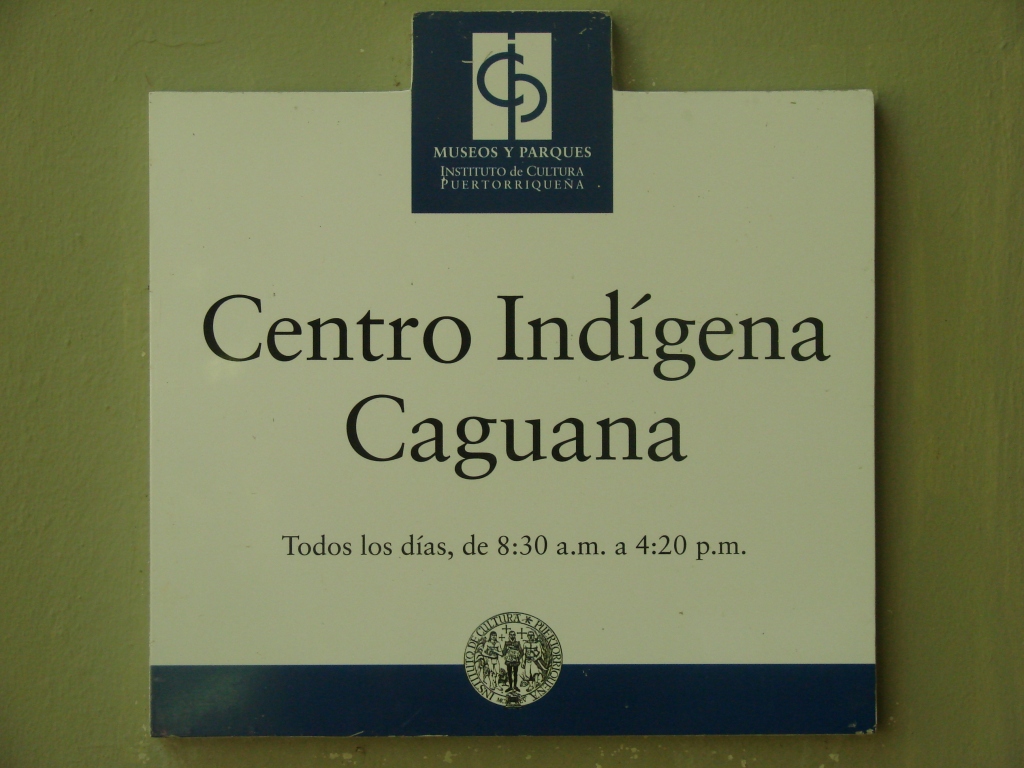

Mi Pueblo Taíno aroused in me an intriguing interest in finding out more about the Taíno tribes of Puerto Rico. This book, less than 200 pages long and which can be read in one day, grabs the reader’s attention through its subtlety and poetry. Once I finished the book I was yearning to go visit what González Muñiz and many other historians consider the most important ceremonial site for Taínos in the island, Parque Ceremonial Indígena de Caguana (Caguana Indigenous Ceremonial Park). This site was discovered around 1915 and many archeologists believe it to be of foremost importance for the Taíno culture just prior to the arrivals of the Europeans. I wanted to walk were the Taínos had walked and see the place where they gathered. I wanted to connect with them by standing where they once stood.

View of the Caguana Indigenous Ceremonial Park

However, I must remind myself not be deceived by the looks of the rich and vast diversity of ethnic features found throughout the peoples of Boriquén. To this day there is still much controversy about the legitimacy of Taíno ethnicity among new generations. Scholars and archeologists argue about the degree and validity of Puerto Rican ancestry traced back to the Taínos. Some say that Taínos in Puerto Rico were totally exterminated by the Spaniards. Others argue that a small number of Taínos fled the island by boat, while others secluded themselves as far away from their oppressors and hid in caves while continuing their cultural traditions.

Three-pointed mountain (El Cemi)

While there is not enough scientific evidence of what really happened to the Taínos in the Greater Antilles, one has to simply ask a local from the island whether he thinks Taíno Indians are extinct. Most would argue that they’re still alive, and that many of them intermarried other races and Puerto Rican ethnicity is a product of that blending.

Now, I have traveled throughout the island of Boriquén on a number of occasions and have a fairly good understanding of Puerto Rican culture. Still, I have to say that visiting Caguana for the first time helped me experience Puerto Rican culture in new and refreshing ways. This trip gave me an invaluable experience worth sharing with others.

Caguana Indigenous Ceremonial Park

Parque Ceremonial Indígena de Caguana is located in one of my new favorite places in the island and, in my opinion, one of the most beautiful towns in Puerto Rico with the most breath-taking views: Utuado. Utuado is located almost in the center of the island, neighboring some of the highest peaks in Puerto Rico. Driving up to Utuado is quite an experience and one that any avid traveler must experience, but it may not be for the faint of heart.

Going up the mountains in Utuado

Driving at 5 miles per hour through winding, single-lane roads and having your ears stuffed up because of the high elevation may make some folks want to turn back around in a heartbeat. But, once you find yourself immersed in the beauty of the mountainous region and see the splendors of the cloud covered mountain tops, anyone will quickly forget about the zigzagging roads. Words are not enough to describe this blissful experience. So much so that, upon returning from my trip from Utuado late that night and attempting to settle down and go to bed, my mind remained wired, savoring and re-experiencing every moment, every vista and every event, that I was hard pressed to fall asleep that night.

Batey (ceremonial indigenous ground)

I visited every site whose pictures I had seen on Mi Pueblo Taíno. The beautiful ceiba trees, which I often read about in every book on Taíno indigenous tribes, were bigger than what I had read or seen before.

ceiba tree, Tainos used it to make canoes

Anyone wanting to learn more about Taíno culture and its indigenous tribes should make the Caguana Indigenous Ceremonial Park a must-see. This is certainly the place where any researcher interested in Taíno archeology and culture should begin his or her research journey.

Batey (ceremonial indigenous ground)

Soon enough, always too soon it seems, my trip to Puerto Rico came to an end. As I sat there on the plane and looked out the window I watched as the island kept getting smaller and smaller. I was in a pensive mood, evaluating, analyzing and meditating on all the wonderful experiences I had during this go around. And of course my visit to Caguana was at the top of that list. I was captivated by the Taíno culture and how much of their legacy continues to play an active, vital role in almost every aspect of Puerto Rican society to this day.

In my opinion, even though Taínos as an ethnic group do not exist today their legacy and culture remain very much alive to this day. My observations, as someone who’s not only an admirer of this great culture but who considers herself an active advocate and supporter for the preservation of our indigenous tribes, that how a person perceives himself in terms of a member of a cultural society is what counts. Most Puerto Ricans see themselves as direct descendants of their Taíno ancestors; regardless of what anyone might argue or what science is able to prove or disapprove.

petroglyph symbolizing a woman

petroglyph depicting a bird

Rafael González Muñiz in his book Mi Pueblo Taíno, shares a thoughtful and provoking poem from Salvador Brau. I feel this poem elegantly demonstrates why the spirit of the Taínos remains alive to this day.

“Vencido por la fuerza, es verdad;

pero, al caer vencido en la arena

del combate el boriquense conquistó

un derecho a la inmortalidad histórica.

Como aquel pueblo cayó no caen los cobardes.”

“Conquered by force, that is the truth;

but by falling down in the sands of combat

the Boriquenses conquered the right to historical immortality.

Even as these people fell to their conquerors

they never did so as cowards.”

© Lizzeth Montejano and Aculturame, 2012-2022. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without expressed and written permission from this blog’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Lizzeth Montejano and Aculturame with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

If you are interested in any of my work (including pictures, text content, etc.) you can contact me at aculturame@gmail.com

If you would like to request permission to use any of my blog content please contact me at aculturame@gmail.com

Look up Internet and youtube the culture still alive today tribe called Guatu’ma’cu a Boriken concilio Taino look it up, most of them has done dna tested.

Thank you for your comment; I appreciate you taking the time to read my blog about one of the most important tribes in the Caribbean, the Taíno. From my own research it seems that the Concilio Taíno Guatu-Ma-cu A Borikén is considered a cultural group that works to preserve the Taíno culture in Puerto Rico. The majority of Puerto Ricans have in their DNA American Indian blood as well as African and Spanish blood; this proves that Puerto Ricans have a mixture of these bloods in their DNA. The original tribes however were decimated by the Spanish, there is no scientific evidence that shows that any tribes were able to survive after the arrival of the Spanish or that any group of Taínos continued to practice the original cultural traditions of the pre-columbian Taíno. Groups like Concilio Taíno Guatu-Ma-cu A Borikén have emerged in the last twenty years to honor and preserve the Taíno traditions that were already lost.

As you may be aware in 2018 scientific proof was found that most of the Indian DNA in Puerto Rico is of Taino stock. This means that they survived the Spanish occupation and have descendants to the current age. So the question is, when does a person stop belonging to a certain ethnic group by mixing? Let us use Blacks in the USA as an example. When do you stop being Black in the USA? At what percentage? 50% 25% 16%, 8% one drop of blood? Most Blacks in the US do not speak an African language or even have many African loan words in their English yet call themselves African Americans. Why does this not apply to those who have Indigenous blood? In Puerto Rico the Jibaro Mountain community still practices planting and harvesting including herb lore or green medicine in the Taino fashion. so yes we are mixed but so are most eastern Indians in the USA and they still retain their identity. In the last census 32,000 individuals claimed Indian identity in Puerto Rico.

Are there any traces of their language. What a pity… Genocide, really.

There are hundreds of everyday words used in our Spanish which are Taino. these words show up in old sayings, in the names of fruits, animals, fishes, flora and fauna. The majority of the towns and Barrios have Taino names and even what we call ourselves as Boricua is a Taino word from the indigenous name of the island. 62% of the population has Taino dna via the mother’s line. and the average amount of percentages is between an eighth and a quarter Indian.

I just saw a story on Facebook about Peruvians reclaiming their indigenous languages, and I think that’s great. They should be protected and taught to kids when they are little. It is a great loss when these cultures are “disappeared” by the dominant culture

That’s very interesting I also been reading many articles about indigenous communities in Mexico and Native American tribes in the U.S. trying to revive and rescue their indigenous languages. The problem they are encountering right now is how do you encourage young people and children to embrace their native language without feeling ashamed of speaking it. There’s still a lot of discrimination against children and teenagers who still speak their native language in Mexico.